Prostitution Today in Rio

Anthropologist Thaddeus Blanchette and historian Cristiana Schettini provide a history of Rio sex in their 2013 paper, Sex Work in Rio de Janeiro: “More than tolerated – effectively managed”.

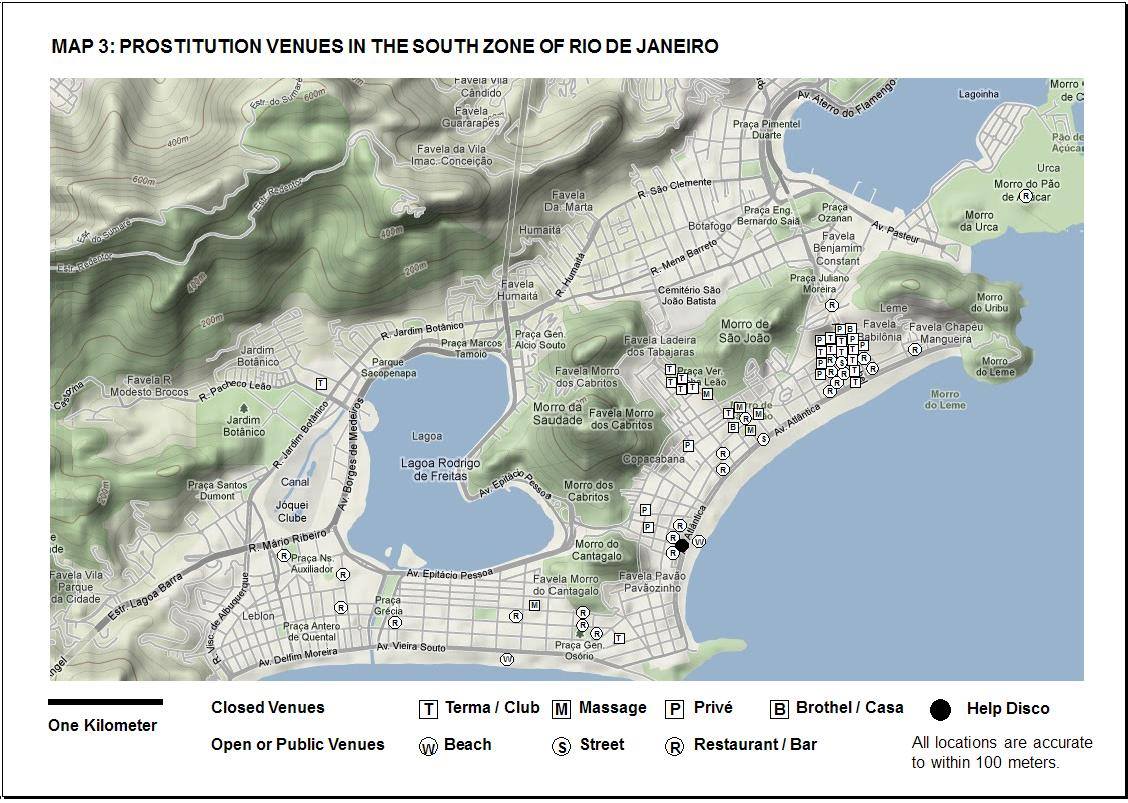

Published to RED LIGHT RIO in six parts, the paper situates Rio’s red light district on the larger map of sex venues in Rio, and in the broader historical context of Rio’s extra-legal regulation of a profession that is not illegal in Brazil.

Part I is a history of sex in Rio.

Part II discusses the fuzzy legality of prostitution in Rio.

This section looks prostitution today in Rio, and presents eviction maps of sex venues in Copacabana Beach and downtown Rio.

Praça Mauá, Copacabana and Downtown

During World War II, prostitution seems to have intensified in the nightclubs and bars around the Praça Mauá port district, perhaps following a boom in shipping brought on by the war, perhaps in reaction to Etchegoyan’s moralizing campaigns in the city’s old red-light districts.

By the late 1960s, it seems to have become Rio’s first example of a prostitution district organized almost exclusively around foreign customers. Describing the huge flows of foreigners through the port region during and immediately following the Second World War, Cezar and Viveiros de Castro claim that these men “were the main clientele of the ‘girls’ of Praça Mauá, who often spoke five different languages – or at least dominated the essential vocabulary of their profession in these languages”.

By the late 1960s, however, the port was beginning to decay and street prostitution became much more common in the neighborhood, as the Mangue began to be demolished. Following the general tenor of moral hygiene and urban renewal which accompanied the early years of the last military dictatorship (1964-85), the police moved in on Praça Mauá and implemented yet another form of unofficially managed tolerance, even as the city began to close down the Mangue Republic .

An article published in 1971 in the newspaper Jornal do Brasil described how the police worked with local club owners (who might have been accused of pimping and lenocínio under other circumstances) to maintain control of prostitution around Praça Mauá:

In his first week in the area as the head of the 1st Precinct’s vigilance group, [Inspector] Cartola said that “I saw that for us to get our job done, we needed to do some public relations work… I brought together all the local business owners who worked the nightlife scene and I split up responsibilities with them”.

…The prostitutes were banned from walking the streets surrounding the square and their professional activities were restricted to closed environments. People could thus walk the streets without being importuned by the whores…. [Cartola continues:] “Another interesting thing is that we’ve had no robberies of johns in our jurisdiction for quite some time now because the club owners themselves are now selecting the women that they’ll allow into their houses”.

This brief story highlights several persistent themes in the extra official regulation of prostitution by the police in Rio de Janeiro from World War II on to the end of the military dictatorship in 1985. In the first place, throughout the 20th century, the sale of sex was largely understood by the police and the judiciary as a professional (if immoral and degraded) activity and not a crime.

Nevertheless, it was seen as an activity that must be tightly disciplined and kept within bounds. Ideally, it should be conducted out of the public view and wholly separate from the population at large, who should not be “importuned by whores”.

In the case of the Mangue in 1954, the prostitutes themselves were organized to administer the houses and provide order, under police oversight. In 1971 in Praça Mauá, it was the owners of the nightclubs who were empowered by the police to fulfill this role, to the point where they were encouraged to choose which women would be allowed into their establishments – an activity that could be (and was, in other times and places in Rio) considered lenocínio.

Praça Mauá thus became established as yet another of Rio’s unofficial police moderated sex work ghettos, where prostitution was tolerated as long as it didn’t interfere with the “morals and good customs” of the greater carioca society. Until very recently (2011), the port zone still contained many of the clubs and cabarets first established there in the 1940s (or their direct descendants), and the region was still catering to foreigners: itinerant seamen, mostly Filipinos, Indians and Chinese.

In 2012, however, the city of Rio began a wholesale “urban renewal” project centered on transforming Praça Mauá into a “festival port” in anticipation of the World’s Cup of 2014 and the Olympics of 2016. Large sections of the neighborhood have subsequently been confiscated and demolished and it is doubtful that much of the region’s sexual commerce will survive the transformation.

A second direction prostitution moved after World War II was back towards downtown (ironically returning to some of the same streets and even some of the same buildings it had been evicted from in the early 20th century) and Rio’s south zone, particularly Copacabana.

One of the effects of the periodic police campaigns against prostitution outside the bounds of the Mangue during the 1940s and ’50s was an increased camouflaging of the sex trade. With the closing of the old rendez-vous and boardinghouses in Lapa and Glória, sex work moved increasing into hotels and private apartments.

According to Inspector Armando Pereira, the number of hotels used specifically for commercial sexual encounters tripled in the city during the 1950s. Prostitutes would make a deal with a hotel owner (often a Spanish immigrant, according to Pereira) and bring clients back from streets or bars, paying the full day’s rent, but only using the room for a couple of hours.

This modification in sex work practices was greatly facilitated by the liberalization in bourgeois sexual mores, which led to supreme court decisions in the 1950s stipulating that hotel owners were not responsible for verifying the marital status of their mixed-sex guest couples.

In spite of a concerted police effort to close down sex hotels in 1959 (which, according to Pereira, brought prostitution almost to a halt everywhere in Rio outside of the Mangue), they continued to proliferate and, by 1967, there were over 500 of them in the city. With the further liberalization in mores and increased female mobility brought about by the Sexual Revolution of the 1970s, sex hotels began to service ever greater numbers of non-commercial couples. Today, they are still very much a part of the city’s sexscape, used by sex workers and non-sex workers alike as places to conduct temporary trysts.

Other forms of sex work were developed to avoid police surveillance and repression during the 1950s, and ’60s. The first bath houses and saunas began to appear in police records during this period. Pereira labeled them “an invert’s [read: homosexual] paradise”, but many catered to heterosexual trade as well.

Today, Rio’s top-end middle-class commercial heterosexual venues are all saunas. Cheap cabarets and “recreational clubs” with floor shows and back rooms for rent also became common meeting spots for prostitutes and clients during this period, as did massage parlors and cheap theaters. All of these types of venues soldier on in downtown and south zone Rio today.

One extremely common new form of prostitution was, like the sex hotels, enabled by women’s new-found mobility and relative sexual liberty. This was the apartment brothel, which began to fill the gap left by the old rendez-vous and prostitution boarding houses in the late 1950s and early ’60s.

As Pereira describes them, these venues were basically 2-3 bedroom apartments rented out to 5-6 young women who were all prostitutes. The women would bring clients home from bars, theaters and cabarets, using the bedrooms for work during the day and living space at night.

Pereira considered this new sort of commercial sexual institution to be particularly frustrating. The police were generally incapable of distinguishing between establishments of this type and apartments rented by the groups of independently living, non-sex working, single females who were increasingly becoming part of the city’s urban scene:

The girls are all artists or dancers. At least that’s what they say.

What was particularly frustrating to Rio’s anti-vice specialists like Pereira, however, was the fact that these new forms of prostitution were massively concentrated downtown and, in particular, the residential, middle-class south zone of Rio de Janeiro: precisely the regions the Mangue was supposed to serve as social prophylactic for. Police attempts to keep prostitution out of the burgeoning new bohemian beach-side neighborhood were particularly fierce.

As we’ve mentioned above, the decadence of Lapa after World War II prompted a drift of a certain portion of Rio’s bohemians (and the prostitutes who served them) towards the Praça Mauá port district.

A much more significant migration, however, began in the 1950s, as the south zone beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema came to be associated with Bossa Nova and the city’s upper class nightlife. The “artistic” prostitution earlier associated with Glória and Lapa was part of this migration, with women establishing themselves in the new nightlife spots such as the Beco das Garrafas (Bottle Alley – a renowned strip of clubs and bars in Copacabana associated with the birth of Bossa Nova).

The new apartment-style mini-brothels, populated by “dancers and singers” were perfect for this new bohemian scene and were almost impossible to completely repress. Pereira recounts a story however, which shows how the police tried and the methods they employed:

In 1958, police authorities in the Second Precinct (Copacabana), who normally have to deal with far too many cases of suspect apartments, decided to clean up one of the dirtiest buildings on R. Ministro Viveiros de Castro…

Many regular families used to live in this building, which also contained a number of suspect [apartments] that operated with prostitutes. For some reason, the number of these later establishments began to suddenly grow… Slutishness became structured, returned good profits the lawyers kept themselves busy covering for the madames and the girls went wanting.

It was necessary [for the police] to act with a certain degree of arbitrariness, use a measured dose of violence, in order to take the madames out. Many of them were illegally imprisoned without warrants… and convinced themselves that it was better to run up the white flag, hand over the apartments which had made them so much money, and move to other parishes, where things were more liberal.

Here we get a tantalizing picture of how the carioca police operated outside the Mangue in the 1950s and ’60s: in order to keep prostitutes out of “regular family” area, they were willing to go outside the law and illegally imprison and perhaps even torture men and women they viewed as “pimps” and “madames”.

This was not to end prostitution, mind, but simply to “convince” said establishments to move elsewhere – most probably the Mangue. Pereira was aware that this sort of operation was entirely illegal, but he was also so convinced of its acceptability to the city’s authorities and the public in general, that he recounts it in a laconic and even humorous tone.

Police attempts to keep prostitution out of Copacabana were doomed to failure, however. The strip described by Pereira in the 1960s as “the aquarium” (the neighborhood’s main prostitution area) became the most concentrated region of Copacabana bars, nightclubs and cabarets in the 1970s and ‘80s.

54 of the 279 commercial sexual venues identified in Rio de Janeiro via ethnographic fieldwork are situated in Copacabana with 26 of these within two blocks of the old “aquarium”. These establishments are also far and away the oldest venues in the neighborhood, so it is quite possible that some of them evolved directly out of the bohemian scene that graced the Copa in the 1950s.

One thing is quite definite, however: by the late 1970s, Copacabana prostitution had begun to increasingly integrate foreign tourists as clients.

The majority of Rio’s luxurious heterosexual saunas and first-rank night-clubs are in the neighborhood and, although foreign clients would never be the majority in most of Copacabana’s prostitution venues, they would dominate the wealthiest and be a considerable presence in others. In 1984, the famous Help discotheque was established, becoming the city’s main focal point for encounters between foreign tourists and carioca prostitutes by the first years of the following decade.

Help was finally confiscated by the state government in 2010 in order to make way for a new Museum of Sound and Imagery (and, of course, as part of the general “hygienization” plans being implemented prior to the World Cup and Olympics).

During its 25 years of existence, however, the disco illustrated the fact that prostitution in Rio – even the forms linked to sexual tourism – continues to exist alongside other forms of commerce and sociability. During the day, the complex surrounding Help turned into a restaurant dedicated to non-sexual tourists. Even in the evenings, when the tables in front of the club began to fill up with prostitutes and clients, half of the sidewalk space was dedicated to a “normal” restaurant.

While Copacabana began to specialize in sexual tourism and the bohemian or “artistic” prostitution that had earlier been Lapa’s métier, downtown Rio de Janeiro in the 1960s and ’70s began to develop a commercial sexual scene geared towards a Brazilian clientelle made up of downtown male workers (of all classes).

This process speeded up considerably as the Mangue became increasingly demolished and its sex-working women driven ever farther away from the center of town. Theater, cabaret and hotel prostitution, as well as massage parlors became quite common, downtown. By the late 1970s and early ’80s, however, heterosexual saunas had also become established in the region, some of them quite posh.

In 2011, ethnographic research conducted by Blanchette and Silva’s in identified 92 commercial sexual venues within a five block radius of the intersection of Ave. Getulio Vargas and Ave. Rio Branco (18 of which were clustered around the port zone around Praça Mauá). Most of these venues are “closed” in the sense that they are out of the public’s direct sight, but in 2011, it was very hard to find a block in downtown Rio that didn’t contain at least one commercial sexual venue.

Urban renewal for the upcoming World’s Cup (2014) and Olympic Games (2016) has sparked a wave of real estate speculation, however, increasing rents all over Rio and, in particular, downtown. As old buildings are torn down or renovated, many of the larger and more established or notorious commercial sexual venues are being evicted.

The smaller venues established in high rises and known locally as “privés” seem to be maintaining a consistent presence in the center, however. A typical privé is set up in an office or an apartment, subdivided into three or four “cabins” with a half dozen women working there. The clientele is principally made up of downtown workers and peak hours for the privés come at noon and 5:00 PM, as work lets out. Privés charge more or less, depending upon the class of men they try to attract, with the cheaper ones selling sex for 25 dollars to 20 minutes and the more expensive variety charging up to 100 dollars an hour.

The privé is an adaptation to Rio’s tradition of extra-official regulation. To a certain degree, it’s a further development of the “apartment prostitution” of the 1950s and ’60s, except that the women who work in them do not also live there. Because privés require little in the way of capital investment, they can pick up stakes and move to a new address when they inevitably encounter police “regulation”.

They must, obviously, maintain delicate relations with their neighbors, who will presumably denounce the establishment if it causes “disorder” in the building. The fact that many privés manage to go for years located in the same apartment, however, shows that, in spite of the repeated attempts of the carioca police throughout the 20th century to segregate prostitution, it is still common for sexual commerce to exist side-by-side with other commercial and even family establishments.

The carioca prostitute today

From the second half of the 20th century on, the division between “Europeans” and “Brazilians” became less demarcated in Rio de Janeiro as immigration dried up following World War II. Internal migration, especially from the northeastern and northern regions of Brazil, began to have a large impact on commercial sex in the city as Rio expanded from 1,500,000 inhabitants in 1930 to some 6,300,000 in 2010. During this period, the rural or small-town girl from the interior of Brazil, came to the big city to make good money and working as a prostitute became a stock figure in literature and the news media.

The growing vocation of Rio as a destination for international tourism from the 1950s on also brought a new and important male client – the foreign tourist – into the city’s sexual/affective markets. This development, together with the increasing sexual liberation of women in urban Brazil, combined with long-extant stereotypes of the nation as exceptionally “hot, tropical and sensual” in order to establish the “Brazilian woman” as a recognized and much-appreciated racialized and sexualized feminine type in the global sexscape.

The figure of the mulatta has become so highly associated with this style of femininity that racial admixture, female sensuality and Brazilianess are now almost synonymous in the international media, with Rio de Janeiro being globally understood as “ground zero” for this phenomenon.

As a result, one can say that there’s been a “mulatta-ization” of popular and media representations of the carioca prostitute, as well as a certain self-identification with the figure of the mulatta – and her historical, symbolical heritage of sensuality, beauty and emotional intensity – among carioca prostitutes.

The negative classification of the lower-class “preta” (black woman) still lives on, however, in the frequent popular association of prostitutes with residency in one of the city’s many favela shantytowns. The urban reforms of the early 20th century failed to resolve Rio’s perpetual lack of working-class housing and, in fact, intensified the problem through the “hygienization” of many poor neighborhoods and the consequent elimination of tenements and other forms of cheap housing. Coupled with the increase in Rio’s population, this situation resulted in the expansion of ad hoc housing solutions on irregularly-occupied lands, often situated on the un-urbanized slopes of the city’s mountains.

In the carioca popular media, the inhabitants of these favelas are racialized as black or mixed and are often stereotyped as the creators of much of the city’s social and urban disorder. The favelas themselves are the source of much anxiety for local elites, who classify them as areas that are beyond the State’s control. The “preta” prostitute – black, poor, impoverished and sexually degraded – can still be seen in the popular media and certain NGOs and policy-makers portrayal of prostitution as a common socio-economic choice of female favela dwellers.

Blanchette & Silva’s ethnographic work, however, suggests that many, if not most, of Rio de Janeiro’s prostitutes do not live in the favelas and are not particularly poor, nor see themselves as black or are seen that way by their clients. The “extremes” of racial classification (black and white) tend to be avoided by carioca sex workers, who generally prefer to classify themselves as “blonde”, “morena” (brown, but also brunette), or mulatta and who will often shift from one category to another in response to their perceptions of client’s preferences.

Today, there is still a large number of diverse types of women conducting sex work in Rio de Janeiro. While it is of course impossible to describe the “average” carioca prostitute with any degree of precision, we can, however, create a Weberian ideal type or, alternatively, a Durkheimian “norm” (in the sense that this type of woman can be found in all commercial sex venues in Rio) for the carioca prostitute at the dawn of the second decade of the 21st century.

It should be understood, as Weber himself emphasized, that as an ideal type, the description below “is formed by the one-sided accentuation of one or more points of view and by the synthesis of a great many diffuse, discrete, more or less present and occasionally absent concrete individual phenomena, which are arranged according to those one-sidedly emphasized viewpoints into a unified analytical construct… ”

As such, it is meant as an idea construct to guide our thinking about the women commonly encountered in prostitution in Rio de Janeiro today: it is not meant to be a statistical average which corresponds in all its characteristics to any one particular case. With that advisory firmly in place, this is what we can say about the ideal typical woman involved in prostitution today in Rio is the following:

She has brown skin and dark hair (often dyed blonde and straightened) and racially classifies herself as mixed.

She was born in the city, more often than not, and lives in the outer working class suburbs.

Her parents are working or lower middle class, with the mother often being a housewife.

She has had a formal education up to the end of high-school, but attended low quality public institutions and probably didn’t go straight through without taking some years off. She probably wouldn’t be able to pass the entrance exams for Brazil’s free federal and state universities.

She began sexual activity between 13 and 16 years of age and often has had her first “marriage” (typically a non-formalized consensual union) before the age of 18.

She is currently in her mid-20s. She is a mother and usually still lives with her family or a sexual/affective partner.

She has held other jobs in both the formal and informal sectors, usually “feminized” work in the service economy such as maid, baby-sitter, checkout clerk, salesperson, beautician, or telemarketer. She got into prostitution as an adult, generally at the behest of a friend or by answering an ad in a newspaper.

Prostitution is by far and away the most lucrative form of employment that she has had in her life, generally paying 4 to 10 times more money than any of her prior jobs. She sees sex work as a way to achieve more than survival and plans on using her gains to attend school, open a business, build a house, or consume luxury items that would otherwise be beyond her means.

She is not a drug addict. She does drink alcohol, but rarely anything stronger than beer or wine.

She isn’t controlled by a pimp and is not forced to work, but if she works in a closed venue she is answerable to that venue’s owner or manager with regards to how many days and hours a week she works and may be fined if she doesn’t show up.

There’s a very good chance that she is an evangelical Christian.

The “ideal typical prostitute” in Rio de Janeiro today is, in short, almost indistinguishable from non-prostitute working class or lower middle class women and the above “type” can be found in all venues of the city, ranging from the cheap “fast fodas” of downtown and Vila Mimosa to the 700 real per hour saunas of the exclusive South Zone.

In fact, while the popular media and policy makers still believe in the “high class” and “low class” model of prostitution encoded in the “French/Pole” dichotomy of the early 20th century, it is very difficult to say, today, that there are clear physical or social types dominating one or another form of carioca sex work.

Obviously, one can find more lower class and less iconically beautiful prostitutes in the downtown “fast fodas” than at an upscale South Zone sauna, but the same general social and physical types can be found almost everywhere sex is sold in Rio. In the words of anthropologist Ana Paula Silva:

What determines price in a commercial sexual venue in Rio today is not the style or beauty of the women so much as the luxury of the surroundings and, more importantly, the social class of the male clients.

Finally, ethnographic work confirms that, even today, the dividing lines between prostitution and other forms of sexual-affective relationships are very often ambiguous and shifting in Brazilian popular culture. Among international sexual tourists, for example, Rio de Janeiro has a reputation of being the place to go for “girlfriend experience” style commercial sex.

These same foreign men also claim that it is easy to convince “normal” (i.e. non-prostitute) working-class cariocas to engage in sexual exchanges for money or “presents” while carioca sex working women affirm that when it comes to foreign tourists “you get paid more as a girlfriend than as a prostitute”.

Read the conclusion of Blanchette and Schettini’s Sex Work in Rio de Janeiro: “More than tolerated – effectively managed” in Part VI: World Cup Sex Panic.

This paper was given at a seminar at the International Institute of Social History as part of their Selling Sex in the City project. It will be published later this year as part of a book dealing with the history of sex work in several dozen global cities, and is republished to REDLIGHTR.IO with permission of the authors and the IISH.

—— References

58 Although certainly foreign tourists and sailors had frequented Rio’s houses of ill-repute in some numbers in earlier decades.

59 P. B. Cezar & A.R. Viveiros de Castro A Praça Mauá p.76.

60 P. B. Cezar & A.R. Viveiros de Castro A Praça Mauá (Rio de Janeiro, 1989) pp.64-76.

61 T. Baltar, P. C. Araujo & A. Jacob “Praça Mauá abriga em 11 boates mercado de sexo para os homens do mar” Jornal do Brasil 7-8 de março (Rio de Janeiro, 1971) p.40.

62 Armando Pereira, Sexo e Prostituição pp.94-95.

63 Ibid, p.100.

64 Ibid, p.104; T. Blanchette & A.P. Silva, “Sexo a um real por minuto”.

65 Armando Pereira Sexo e Prostituição p.102-103.

66 Waldyr Abreu, O submundo do jogo de azar, prostituição e vadiagem p.130; Marcello Cerqueira Beco das Garrafas: Uma Lembrança (Rio de Janeiro, 1994).

67 Armando Pereira, Sexo e Prostituição p.102, footnote 1.

68 Ibidem.

69 T. Blanchette & A.P. Silva ”Prostitution in Contemporary Rio de Janeiro” in Dewy, S & Kelly, P. (orgs.), Policing Pleasure: Sex Work, Policy and the State in Global Perspective (New York, 2011). It should be noted that Blanchette & Silva count as a “venue” each discrete address or moral region where prostitution takes place. Thus, Vila Mimosa’s 78 separate micro-establishments are counted as “one venue”, as are many downtown and Copacabana buildings that contain more than one commercial sex establishment.

70 By “global sexscape”, we follow Denise Brennan’s lead in applying ArjunAppadurai’s understanding of global flows of information, capital, imaginings and peoples to the sexual and affective sphere. Denise Brennan, What’s Love Got to Do With It? Transnational desires and sex tourism in the Dominican Republic (Durham, 2004); Arjun Appadurai “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Culture Economy” IN: Featherstone, Mike. Global Culture: Nationalism, Globalization and Modernity (London, 1990).

71 Maurício Abreu A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro, 2006).

72 T. Blanchette & A.P. Silva ”Prostitution in Contemporary Rio de Janeiro” pp. 130-145; “Amor a um real por minuto: a prostituição como atividade econômica no Brasil urbano”. In Correa and Parker, orgs. Sexualidade e política na América Latina: histórias, interseções e paradoxos (Rio de Janeiro, 2011)

73 This ideal typification is based on 48 formal interviews conducted by Blanchette & Silva with carioca sex workers in a wide variety of commercial sex venues, as well as 8 years of participant-observation in Rio’s sex work involving thousands of non-structured, informal interviews with (as of 12.2012) 287 sex workers, among other sources.

74 Max Weber, The methodology of the social sciences (New York: Free Press, 1997 [1903-1917]). p.90.

75 “Foda” means “fuck” in Portuguese and the term “fast foda” is used by local clients as a riff on “fast food” to describe the kind of commercial sexual venue which charges about 1 real (.50 USD) per minute for 15-30 minutes of sex.

76 By “iconically beautiful”, we mean the sort of beauty that is promoted by commercial advertisements and popular erotic magazines such as Playboy: i.e. large secondary sexual characteristics, thin body, long straight hair, lighter skin, etc.

77 Ana Paula Silva, “’Cosmopolitanismo tropical’”.

78 T. Blanchette & A.P. Silva “Nossa Senhora da Help: sexo, turismo e deslocamento transnacional em Copacabana” Cadernos Pagu n.25 (Campinas, 2005) pp. 249-280 ; Adriana Piscitelli, “On ‘Gringos’ and ‘Natives’: Gender and sexuality in the context of international sex tourism in Fortaleza, Brazil”. In Vibrant, Ano1, V1. (2001).

79 According to Elizabeth Bernstein, a commercial sexual experience where what is sold is a manufactured authenticity that tries to simulate reciprocal desire and pleasure. Elizabeth Bernstein Temporarily Yours: Intimacy, Authenticity, and the Commerce of Sex (Chicago, 2007) pp.125-130.

80 T. Blanchette & A.P. Silva “Nossa Senhora da Help” pp.277-278.