Prostitution in Rio: “Not Illegal”

Anthropologist Thaddeus Blanchette and historian Cristiana Schettini provide a history of Rio sex in their 2013 paper, Sex Work in Rio de Janeiro: “More than tolerated – effectively managed”.

Published to RED LIGHT RIO in six parts, the paper situates Rio’s red light district on the larger map of sex venues in Rio, and in the broader historical context of Rio’s extra-legal regulation of a profession that is not illegal in Brazil. Part I is a history of Rio sex. This section discusses the fuzzy legality of prostitution in Rio.

Legal Definitions

Brazilian legislation has been cautious with regards to commercial sex and has formally concentrated upon repressing the exploitation of prostitutes rather than repressing prostitution itself. However, the laws themselves are written in such a wide and vague fashion that effectively criminalize any social relation involving prostitutes. This power has historically been utilized by the carioca police to effectively manage prostitution without ever instituting formal regulation.

The Imperial Criminal Code of 1830 makes only one reference to prostitutes: it reduced the penalty for rape to a maximum of one year if the victim was adjudged to be a prostitute. In the case of rape of “honest” victims, imperial law stipulated a sentence of up to twelve years. The First Republic’s penal code (1890), however, was inspired by German legal tradition and incorporated lenocínio as a crime, considering it to be an attack upon “public customs and morality”.

It thus became illegal in Brazil to “excite, favor, or facilitate the prostitution of another in order to satisfy dishonest desires and lascivious passions”, criminalizing intermediaries such as brothel owners and managers, madams and other agents, but officially touching neither prostitutes nor their clients.The behavior of prostitutes thus became the focus of police regulation and this vigilance was typically exercised at the level of the individual precinct house, creating a wide field for discretionary action which would be disputed by the prostitutes themselves.

The 1890 penal code also criminalized inducing “women, either through the abuse of their weakness or misery, or through threatening or intimidating them, to become employed in the traffic of prostitution”. The law specifically targeted pimps but could also be used to penalize anyone who ended up recruiting women for prostitution, independent of whether they involved themselves in the economic exploitation of said women.

Finally, the new republican code declared it illegal to “give assistance, housing, or aid to prostitutes, on one’s own or through others, in order to profit, directly or indirectly, from this sort of speculation”. These laws placed the owners of places where prostitutes worked or lived under the gimlet eye of the law, but could also be used to attack prostitutes’ roommates or family members.

As the decades passed, the republican legal code gave rise to a form of jurisprudence in Brazil regarding the status of prostitutes, criminalization and social stigmatization and the permissible activities of the police. Although this body of law did not formally regulate commercial sex, it was used to repress “suspect” sexual encounters which took place outside the bounds of matrimony in bars, hotels, rented rooms and womens’ homes, while simultaneously tolerating and even extra-legally regulating de-facto red light districts in certain regions of the city. In effect, it laid down the foundation stones for an extra-official form of prostitution regulation that is still very much present in Rio de Janeiro today.

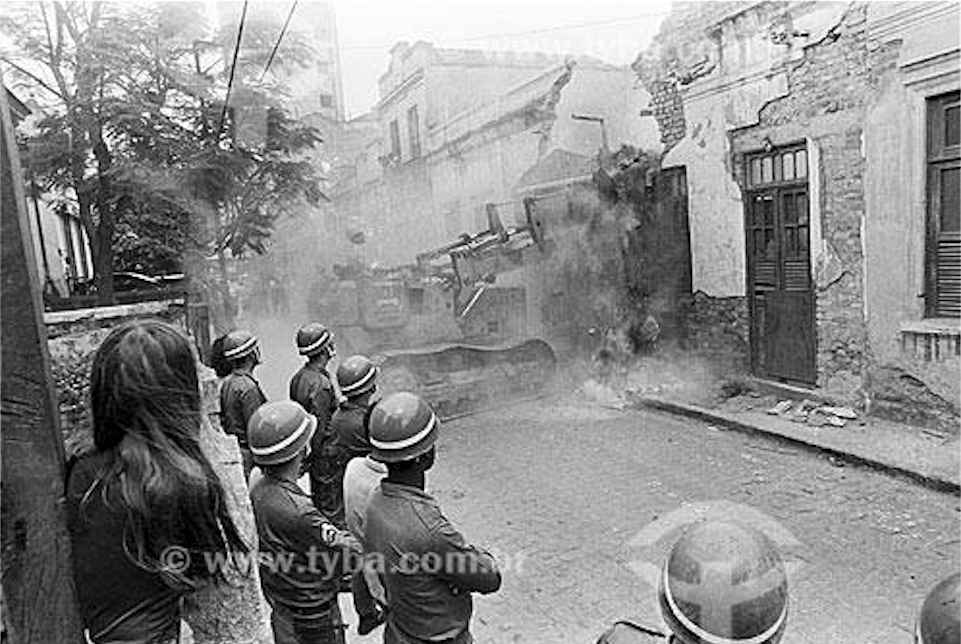

In the first years of the 20th century, laws regarding lenocínio were successively altered to become wider in scope, principally through the pressure from international congresses regarding “white slavery” and the traffic in women. Changes made in 1915, for example, allowed the owners of temporary lodgings (who rented rooms by the hour to a public which was not at all exclusively composed of prostitutes) to be charged with lenocínio. Many female owners of “rendez-vous houses” were likewise arrested in the 1920s and precinct captains took advantage of the new laws to prohibit the establishment of rendez-vous along certain streets, especially in the districts targeted by the city’s urban reform and hygienization plans. The early 1920s also saw perhaps the largest and most consistent attempt to segregate prostitution in Rio de Janeiro: the establishment of the Mangue red light district along what was then the northern margin of town.

The 1940 Penal Code, established by the Vargas dictatorship, defined lenocínio according to five different modalities: mediation or favoring of prostitution, the maintenance of a house of prostitution, ruffianism and trafficking in women (Campos Júnior, 1943). An analysis of the complex and contradictory application of these laws aids us to understand how prostitutes and agents/pimps/procurers/ruffians were defined and understood by the Brazilian state.

While commercial sex itself was neither regulated nor criminalized, its activities were defined, circumscribed and controlled according to a complex of laws which linked prostitution to prohibited forms of labor and habitation and which took in a wide spectrum of people who could be charged with directly or indirectly benefiting from the labor of prostitutes and who could thus be accused of being pimps.

This basic legal orientation continues in place in today: although prostitution is still not illegal and continues to be unregulated in Rio, a series of activities surrounding sex work are criminalized. Thus, when authorities wish to crack down on prostitutes, they can quite easily do so by inciting the police to enforce the laws pertaining to lenocínio.

This situation has resulted in the repression and regulation of prostitution throughout the 20th century. This has been carried out without a specific legal mandate, but under the aegis of widespread social stigmatization of prostitution which effectively cedes to the police large discretionary powers when it comes to dealing with sex work. Stigmatization of sex work is so intense in Rio that, even today, many city officials will erroneously claim that is illegal.

However, at the same time, the non-criminalization of prostitution itself offers the police a convenient reason to ignore prostitution when the sale of sex occurs within the spaces and times in which it is socially tolerated. Thus, for example, the police have a legal excuse (“closing a brothel”) to crack down on the city’s luxurious upper-class bath houses the week before a large international ecology festival occurs in Rio, while ignoring the venues during the other 51 weeks of the year.

Read on Blanchette and Schettini’s Sex Work in Rio de Janeiro: “More than tolerated – effectively managed” in Part III – Prostitution Markets and Sanitation Campaigns.

Featured image: Destruction of the Mangue, 1977 (via Thaddeus Blanchette)

This paper was given at a seminar at the International Institute of Social History as part of their Selling Sex in the City project. It will be published later this year as part of a book dealing with the history of sex work in several dozen global cities, and is republished to REDLIGHTR.IO with permission of the authors and the IISH.

—– References

12 Roughly, “maintaining a brothel”, but also including diverse forms of working as a go-between for prostitutes and clients.

13 Cristiana Schettini Que Tenhas Seu Corpo pp. 171-173.

14 Ibid, pp.195-200.

15 For an excellent example of this in another Brazilian urban context, see José Miguel Nieto Olivar Devir Puta – Políticas da prostituição de rua na experiência de quatro mulheres militantes (Rio de Janeiro, 2013).